4. THE ENDURING PRESENCE

OF THE EUCALYPTUS TREE:

A PHOTO ESSAY

Author

Endangered Yellow-Box – Blakeley’s Red Gum, Grassy Woodland Habitat, Canberra, ACT.

I. Belconnen Woodlands Corridor, Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country

I. Belconnen Woodlands Corridor, Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country

Image 1

Paddock trees within grazed, open native grassland at the edge of the city of Canberra with the Brindabella Range beyond. The traditional First Nations custodians of the land, the Ngunnawal and Ngambri communities, would have conducted ‘cool burns’. Cultural burning was a form of land management, which slowly burnt the grassland but did not reach the top of larger canopy trees, with the intention of encouraging hunting grounds for kangaroo, wallaroo and possums, once important food sources. Marsupials have now returned to these reserves, after largely being displaced by the grazing of cattle and sheep for over a century.

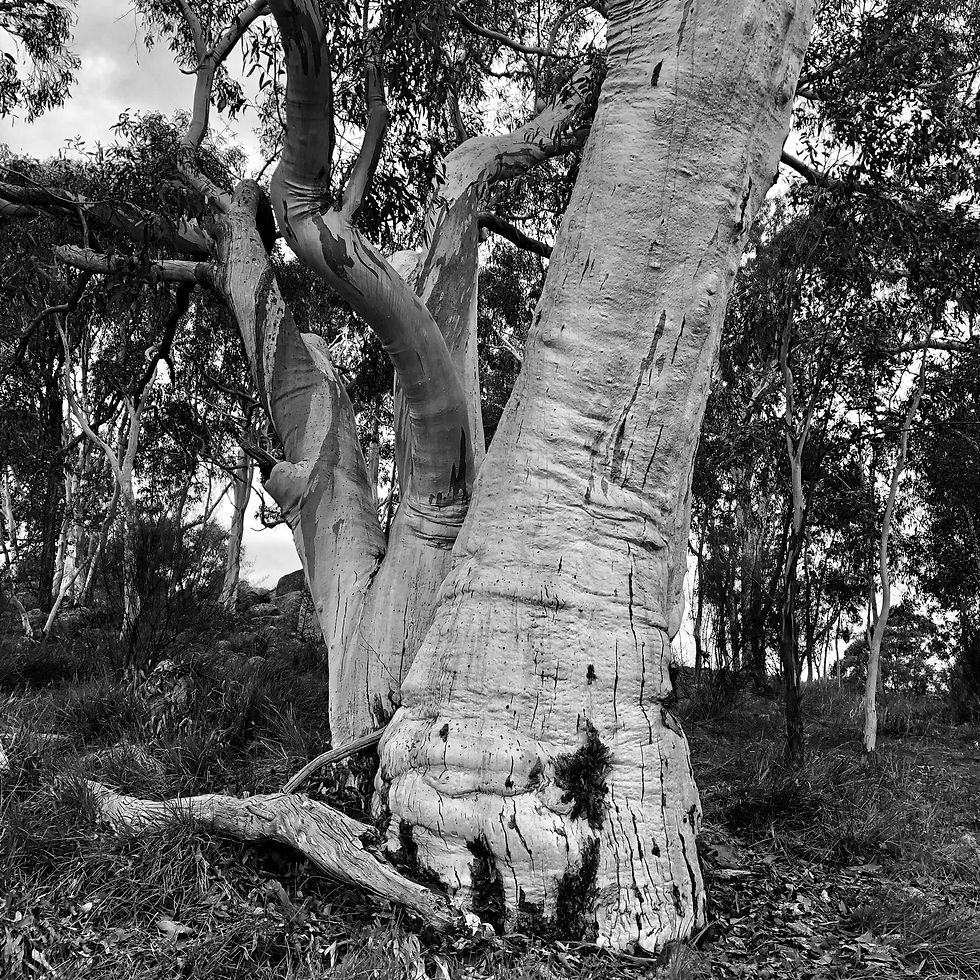

Image 2

The eucalypt, or gum tree, is a means of connection with a deep past. When I see the large girth of a canopy tree, I think of the centuries it took to reach that size with separate trunks diverging to make up a unique individual being, patiently standing over many human generations, while engaging at an incremental pace with the surrounding soils, vegetation and foraging or nesting animals.

Image 3

A Ngunnawal family group may have walked by these two leaning trees centuries earlier, perhaps utilising the bark of the tree for a canoe, or as a coolamon to hold a baby, or grain to make dough. The loop in the tree on the left could be a sacred ‘ring’ tree. An individual may have bent the young branches to form a loop, functioning to signal the direction of an important ochre site, or sacred place to passers-by.

Image 4

The Kama and Pinnacle Reserves were previously farmed, but they are now an important ecological corridor between the Lower Molonglo River and the Belconnen Woodlands, consisting of rare Yellow Box – Blakeley’s Red Gum Grassy Woodland, forming key breeding habitat for local populations of rare gang gang, superb, swift and turquoise parrots. In this image two sulphur-crested cockatoos (lower-middle area of image) are guarding a hidden nest-hollow within a shaded branch of a Blakeley’s red gum (Eucalyptus blakelyi).

Image 5

Two multi-limbed apple box (Eucalyptus bridgesiana) reach out and support one another. Large canopy trees communicate with one another, particularly through their root systems and fungal networks beneath the ground. One large tree may be the ‘Mother Tree’ to hundreds of surrounding saplings that spring up in areas that are not grazed too heavily by ungulates or marsupials.

Image 6

A lone canopy tree stands sentinel surrounded by grassy paddock with the Pinnacle Reserve beyond. Early settlers were drawn to open areas of grassland with just a few canopy trees. The select trees that have remained still standing are those that the farmer spared, perhaps as shade for stock, but often when the landscape was deemed too hilly, boggy or rocky to be productive as good grazing land.

Ngunnawal/Ngambri Country

2. Ginninderry Suburb Construction, 2021

2. Ginninderry Suburb Construction, 2021

Image 7

Brand new, tightly-packed, quick-build homes are a mere blip in the time-frame of the lives of these two enduring Eucalypts. On the edge of the fast-growing capital city of Canberra, Ginninderry suburb is in the process of being developed (a partial Aboriginal name with an English ending, named after a nearby creek).

Image 8

Single paddock trees that would have not long ago been surrounded by grassland remain a stalwart presence, whilst relentless human settlement continues unabated, with newly formed concrete paths forming distinct lines and boundaries. One dead trunk has been left in place in an attempt to provide habitat for wildlife, yet the presence of this dead tree is also a reminder of the trees that have been felled in the name of progress.

Image 9

A maintenance worker is maintaining the introduced grass with a whipper-snipper, effectively not allowing the canopy tree to produce saplings as offspring for future generations. These same trees will not be replaced naturally, but eventually substituted by human-propagated trees from elsewhere.

Image 10

An individual Eucalypt leans at an angle, even though the neighbouring trees that it grew up amongst are no longer present. Now there is mulched up Eucalypt bark from other dead eucalypts spread across the ground to prevent any weeds from appearing, while the tree is being surrounded by new residential housing, lighting, electricity, concrete paths and roads.

Image 11

Makeshift fencing, as bounded safety for any human presence, with newly formed roads and edging are now surrounding the scattered canopy trees that have been allowed to remain in this rapidly changing, managed landscape.

Image 12

High-voltage powerlines running right through the new suburb are the new prominent figures, dominating over the centuries-old paddock trees as sentinels in the landscape.

The presence of individual eucalypts

The photo essay comprises a series of images with accompanying text in the form of explanatory captions, the combination helping to build a multispecies story. Here, the intention is to highlight how the photo essay can be effective in allowing for more-than-human subjectivity and agency. All human cultures rely on language to communicate, but to engage beyond the human it is necessary to pay attention to cues beyond language and, therefore, not to rely on written text alone. The focus on individual eucalypt trees within this photo essay, is an extension of my connection with individual trees and is a part of my ongoing creative expression of sensorial and multispecies entanglements with significant others (see Fijn and Kavesh, 2023).

During the coronavirus pandemic, when the state government imposed a lockdown in September-October 2021, residents in the Australian Capital Territory (ACT) were allocated one hour of outdoor exercise per day. I used this time to walk in local reserves or explore new places through a form of multisensorial auto-ethnography. My photographic series featuring individual trees was partly inspired by an exhibition at the State Library of Australia that I had been to over a decade prior. The series by photographer Jon Rhodes, ‘Cages of Ghosts’ (2007), featured large-format images of scar trees bounded within cages (or as protection from vandalism).

During 2021 I was also a participant in the Bundian Way Arts Exchange programme, run by the School of Art and Design at the Australian National University. Members of the Canberra arts community signed up for the programme to learn from local Indigenous knowledge holders and arts practitioners in the region with the aim for the connections to contribute toward some form of individual artistic output. Usually the course is fieldbased, but, due to travel restrictions during the pandemic, we were limited to Zoom meetings alone. One of the speakers was Paul House, a proud Ngambri man. He talked about his family’s intergenerational presence in the Canberra region, including during significant political moments in Australia’s history. He continues the carving of Aboriginal designs on individual eucalypts as an important ceremonial act. (1)

The concept of one’s homeland is perhaps universal to all mammals. In Aboriginal Australia one’s clan land and the totemic beings that are part of this land are referred to as being on Country. In Mongolia, the term nutag is important on multiple scales, as the homeland that herding families and their herds migrate within, but also encompassing one’s homeland on a national level. Having not been born on Australian soil, this time of travel restrictions was a means for me to explore Canberra as a place. Unable to travel to my own homeland of Aotearoa/New Zealand, or to travel into the field in Mongolia, it meant that connecting with these significant, large eucalyptus trees helped to deepen my connection to Australia as a place. I do not view where I live in Canberra as my homeland or as my connection to Country, but it is my current home. I have developed a newfound respect for individual eucalypts where I live.

Although the eucalypt, or gum tree, is iconically Australian, many Australians do not revere these trees but instead have an overriding fear of them and prefer that they are planted nowhere near buildings. Eucalypts are prone to kill people by dropping large limbs and were thus referred to as ‘widow makers’ in the past. After a severe weather event, such as a storm, or if under stress during drought, their adaptive strategy is to drop a limb as a means of survival. I admire this trait in them, just as I do the skink’s ability to leave a tail behind and regrow a new one. I am mindful of the threat of dropping limbs from above while camping, just as I have to be mindful to avoid standing on a venomous snake when walking through long grass in Australia. Eucalypts are remarkable at regrowing after being burnt by fire, as new stems and branches sprout up from what looks like an old, dead stump. Large Eucalypts can be around 300-400 years old, while mallees have been recorded as being up to 900 years old. When the top of the mallee tree is burnt, the old roots can produce new shoots. (2)

Historian Bill Gammage and writer Bruce Pascoe have successfully made the wider Australian public aware that before settlement the land was carefully managed by Aboriginal peoples across the Australian continent, including through the method of seasonal cultural burning (Gammage and Pascoe, 2021). Before settlement there were already large tracts of grassland that First Australians would walk through unimpeded, with scattered prominent eucalypts.

Prospectors searching for land came to the Canberra region only around 200 years ago, whereas communities of Aboriginal people, the Ngunnuwal (or Ngambri), had been living in the area continuously for more than 20,000 years. In 1817 Oxley described the following scene: ‘[T]he country was broken in irregular low hills thinly studded with small timber, and covered with grass: the whole landscape within the compass of our view was clear and open, resembling diversified pleasure grounds irregularly laid out and planted…’ (Oxley, 1817, cited in Gammage, 2011: 44). When surveyor Robert Hoddle later travelled to the broad Monaro Plains in 1832, he witnessed open grassland and fine trees of Blakeley’s Red Gum, Ribbon Gum, Apple Box, and Yellow Box trees on lighter soils with native kangaroo grass beneath (Gammage, 2011). Ngunnawal, therefore, had been actively promoting the scattered stands of large eucalypt trees. Some of the reserves that I walked through in 2021 still resembled these descriptions. To me, large ‘paddock trees’ are a sign of a lasting presence: they were already there when Ngunnuwal were walking past, utilising their bark to make into various objects and to perform ceremonies, forming what are now known as ‘scar trees’.

Anthropologist Francesca Merlan writes how the Manggarrayi of the Roper River Region in the Northern Territory linked specific individual trees to people, or ancestors: ‘it is meaningful for a member of the [Mangarrayi] society to talk about links between trees and persons, even to the extent of saying that a certain tree “is” a certain person’… ‘Only certain trees of any species represent people; these are inevitably older ones that have not grown visibly during a human lifetime’ (Merlan, 1982: 162).

The cultural attitude toward eucalypts by settler Australians, however, was and still is quite different. Large tracts of land were cleared of vegetation to make way for introduced grasses and allow for the grazing of sheep and cattle, replacing whole grassy-woodland ecosystems. The easiest way for farmers to get rid of trees when clearing the land was to ringbark them, which involved cutting a deep wound right around the trunk, resulting in the tree slowly dying while still standing; while forests of eucalypts were sawed down as timber for building the nation’s capital. With very few grassy-woodlands with yellow and apple box eucalypts left across the wheat-belt of eastern Australia, farmers are now realising the importance of conserving the last remaining paddock trees, as important shade for livestock during the heat of summer, but also as important nest habitat for native birds and marsupials (Fijn et al., 2019).

The series of images forming the photo essay above are in black-and-white as a means of tapping into this window on the past. The intention of the contrast is also to draw out the silhouette and unique structure of each individual tree. When walking through the Belconnen Woodlands Corridor, one can envisage the presence of the First Australians who may have walked past these same trees, living a different way of life by hunting and gathering on the land; followed by farmers with the introduction of strange new species and the grazing of sheep; to now, where these same trees are now being conserved as rare stands within reserves, or have been spared as the few remaining sentinels surrounded by rapidly encroaching residential development to accommodate a burgeoning human population in the nation’s capital. The two sections within the photo essay are not meant to be in opposition to one another, as both are interconnected through being a part of Ngunnuwal/Ngambri Country. There is a need to recognise that reserves and encroaching urban development were originally part of the same grassy-woodland ecosystem.

Figure 1

Eucalypts as ancient sentinels on the edge of a Canberra suburb. Individual image in black-and-white. Photo by the author, 2021.

Artnographic statement

My fieldwork has predominantly been based in both Australia and Mongolia, while an ongoing focus has been on cross-cultural perceptions and biosocial connections with significant animals. An integral part of my research involves the communication of academic output through visual material, integrated with accompanying text. The recording of ‘data’ in the field has often been through an observational form of filmmaking, inspired by mentors based in Australia, particularly David MacDougall’s (2006) and Ian Dunlop’s approaches to filmmaking (see Fijn, 2019).

As I mainly engage with multispecies contexts, this has required a different style from more human-oriented filmmaking, employing what I have referred to as etho-ethnographic filmmaking: a combination of natural history with ethnographic filmmaking techniques (Fijn, 2012). In keeping with a broader observational filmmaking style, I edit images down from a large number of images, but the shots I take in situ are representative of what my eye sees.

I have also been interested in exploring creatively with photo essays in a multispecies-ecological context. Within a multimodal volume on the theme of fluids and medicine, my individual contribution stemmed from field research focusing on the transfer of knowledge surrounding Mongolian medicine. Through three ethnographic vignettes, employing text, images and video, I focused on herders’ use of Mongolian bloodletting techniques on horses as a means of building immunity and preventing illness (Fijn, 2020).

In relation to Australia, for many years I have drawn inspiration from the philosophical writings of Val Plumwood. I published a photo essay, ‘A Shadow Place: Plumwood Mountain’ (Fijn, 2016) where, through just five images, I tried to convey the feeling of encountering the driveway up to Plumwood Mountain, as a means of exploring Val Plumwood’s (2008) concept of a ‘shadow place’. (3) Plumwood would refer to plumwood trees (Eucryphia moorei) as individuals with distinctive, often human like, characteristics, such as the trunk taking on the form of a person with long limbs.

I photographed the Plumwood Mountain forest and the regeneration of the canopy trees after fire swept through the property on 19 December 2019, forming a juxtaposing narrative between my experience of the very real effects of climate change and a similar observational form of documentation by my Grandfather, through the photographs he took 75 years earlier at the end of World War II in Maastricht, the Netherlands. The exhibition was held at PhotoAccess in Canberra in February 2022, entitled ‘Between Hope and Despair’. In this dialogue between my grandfather and myself, I experimented with black-and-white as an artistic form of output in this context too, as it enabled me to extend across generations and across time. (4)

In the present photo essay, the viewer can gain an immediate explanation in the form of individual captions, but can choose whether to read each accompanying caption or not. In that sense, the integration with text is similar to an exhibition in an art gallery or museum space, where the viewer may engage only with the images or can read the accompanying text for more details, but at their own pace. In contrast, with films or video installation, the maker decides upon the depth and speed at which the audience engages with the work (Figure 1).

-

Fijn, Natasha. 2020. ‘Bloodletting in Mongolia. Three visual narratives’. In N. Köhle and S. Kuriyama (eds). Fluid Matter(s). Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body. Asian Studies Monograph 14. Canberra: ANU Press. https://press-files.anu.edu.au/downloads/press/n7034/html/05-bloodletting-in-mongolia/index.html

-

Fijn, Natasha. 2019. ‘The multiple being: multispecies ethnographic filmmaking in Arnhem Land, Australia’. Visual Anthropology 32 (5): 383–403.

-

Fijn, Natasha. 2016. ‘A shadow place: Plumwood Mountain’. Landscapes: The Journal of the International Centre for Landscape and Language 7 (1). Retrieved from https://ro.ecu.edu.au/landscapes/vol7/iss1/12

-

Fijn, Natasha. 2012. ‘A multispecies etho-ethnographic approach to filmmaking’. Humanities Research 18 (1): 71–88.

-

Fijn, Natasha and Muhammad A. Kavesh. 2023. ‘Towards a multisensorial engagement with animals’. In Phillip Vannini (ed.) The Routledge International Handbook of Sensory Ethnography. London: Routledge.

-

Fijn, Natasha, Michelle Young and David Lindenmayer (eds.) 2019. Learning from Experience: Conversations with Family Farmers from the Woodlands of Southeastern Australia Canberra: Sustainable Farms, ANU.

-

Gammage, Bill. 2012. The Biggest Estate on Earth: How Aborigines made Australia. Australia: Allen and Unwin.

-

Gammage, Bill and Bruce Pascoe. 2021. Country: Future Fire, Future Farming Australia: Thames and Hudson.

-

Köhle, Natalie and Shigehisa Kuriyama (eds). 2020. Fluid Matter(s): Flow and Transformation in the History of the Body. Asian Studies Monograph 14. Canberra: ANU Press.

-

MacDougall, David. 2006. The Corporeal Image: Film, Ethnography and the Senses. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

-

Merlan, Francesca. 1982. ‘A Manggarrayi representational system: environment and cultural symbolization in northern Australia’. American Ethnologist 9 (1): 145–66.

-

Plumwood, Val. 2008. ‘Shadow places and the politics of dwelling’. Ecological Humanities 44. http://australianhumanitiesreview.org/2008/03/01/shadow-places-and-the-politics-of-dwelling/

-

Rhodes, Jon. 2007. Exhibition. ‘Cage of Ghosts’. Canberra: National Library of Australia.

-